It’s Time to Consider Upgrading to macOS 11 Big Sur

We’re cautious when it comes to recommending upgrades to new versions of macOS. Apple makes the upgrade process easy—though it can be time-consuming—but upgrading can create workflow interruptions, render favorite apps inoperable, and have other consequences. At the same time, it’s important to stay in sight of the cutting edge for security reasons and to take advantage of advances from Apple and other developers. Upgrading is not an if question; it’s a when question.

We’re not saying that everyone needs to upgrade to macOS 11 Big Sur now, but if you want to, it should be safe now that Apple has released several bug-fix updates. However, there are still a few caveats, and preparation is essential.

Reasons Not to Upgrade

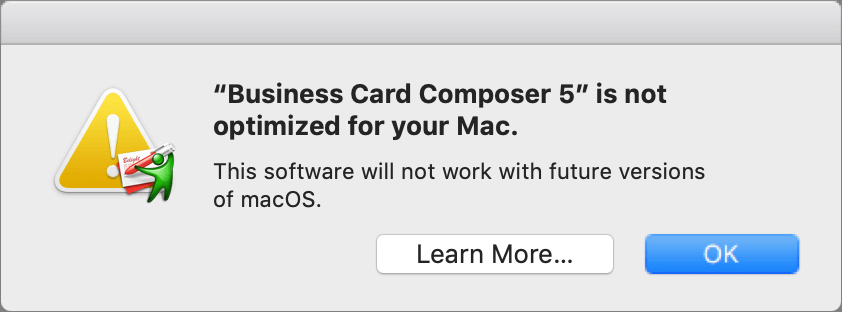

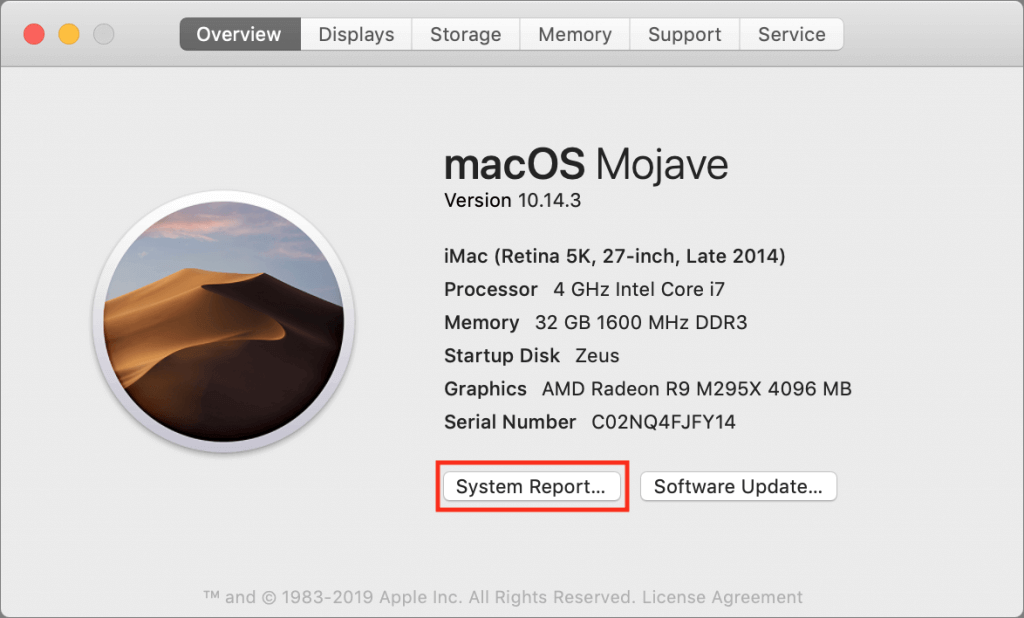

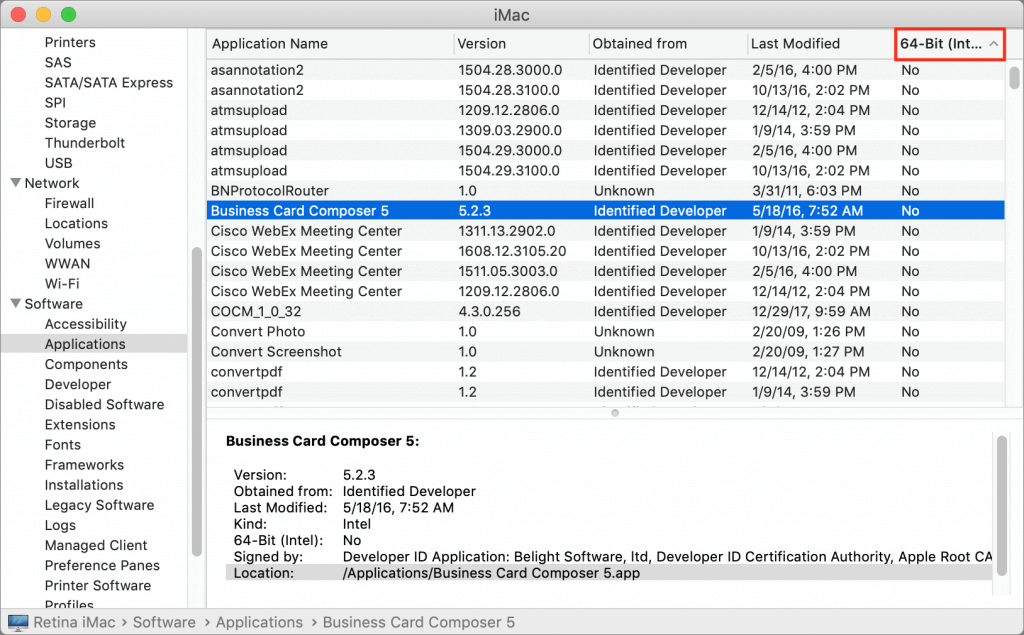

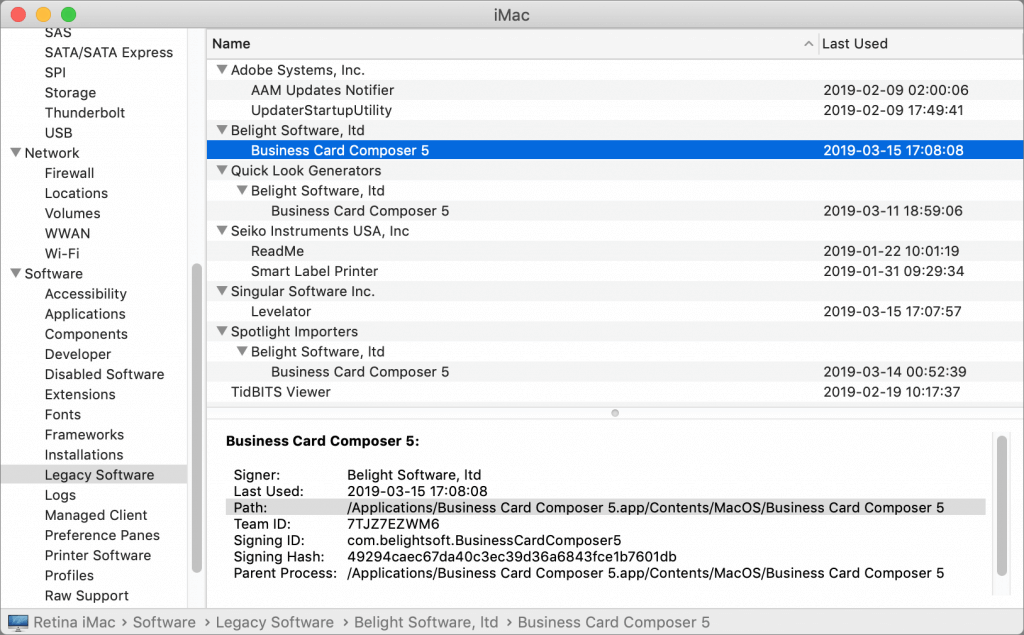

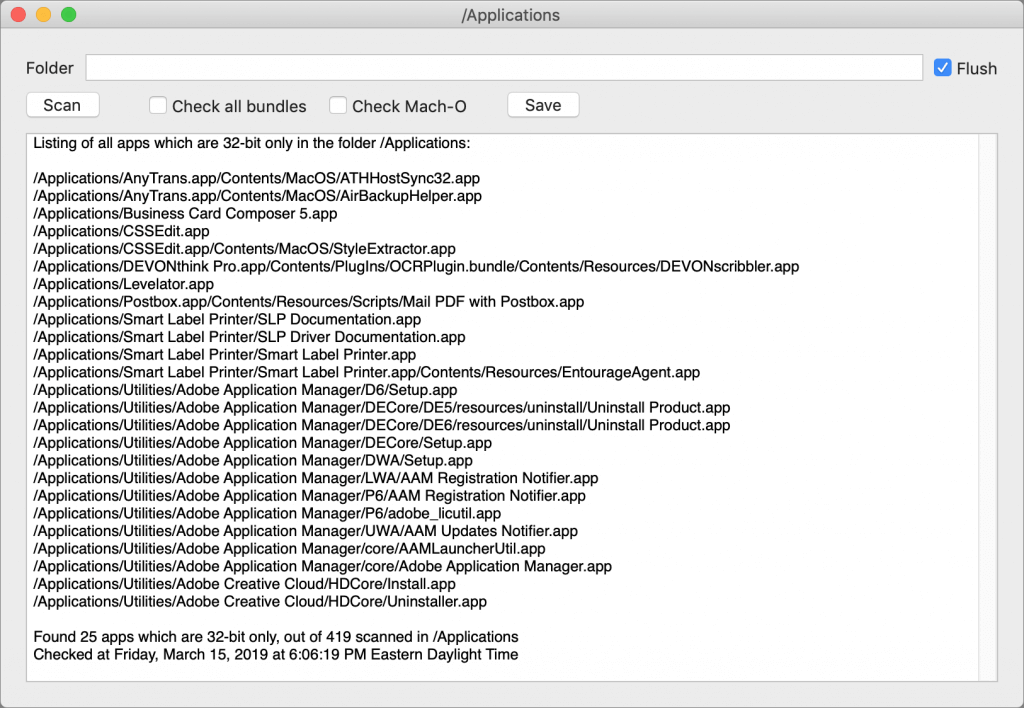

Some people should continue to delay upgrades to Big Sur due to software incompatibilities. Most software under steady development will have been updated for Big Sur by now, but some workflows rely on older versions of apps where an upgrade isn’t practical or possible (ancient versions of Adobe Creative Suite, for instance), or on obsolete apps that will never be updated. You may be able to learn more at RoaringApps, but those who haven’t yet upgraded past 10.14 Mojave may have to upgrade or replace 32-bit apps that ceased working starting with 10.15 Catalina.

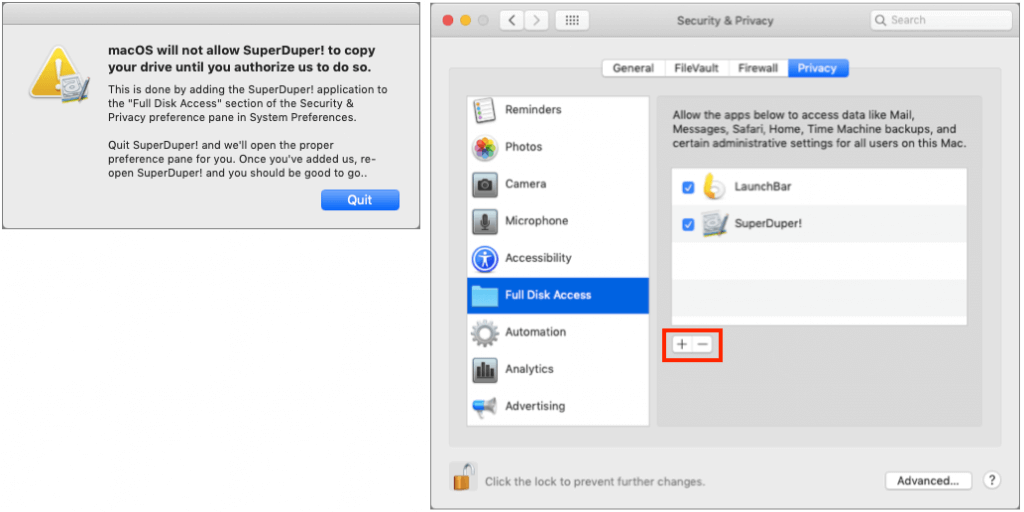

The other app category that continues to have trouble with Big Sur are backup apps that make bootable duplicates. Catalina moved macOS to its own read-only volume, and Big Sur goes a step further by applying cryptographic signatures that make it even harder for an attacker to compromise the operating system. Unfortunately, that also makes creating a bootable duplicate difficult. Carbon Copy Cloner and ChronoSync have developed workarounds; SuperDuper remains incompatible at this point, although an older version can create data-only backups. If you rely on one of these apps for critical backups, make sure you know what you’re getting into before upgrading or reassess your backup strategy.

Before You Upgrade

Once you’ve decided to upgrade to Big Sur, you have three main tasks:

- Update apps: Make sure all your apps are as up-to-date as possible. If you regularly put off updates, now’s the time to let them complete so you have Big Sur-compatible versions.

- Clear space: Big Sur needs a minimum of 35.5 GB to upgrade, and as of macOS 11.2.1, the installer won’t proceed unless there’s enough space. Don’t cut this close—you should always have at least 10–20% free space for virtual memory, cache files, and breathing room.

- Make a backup: Never, ever install a major upgrade to macOS without ensuring that you have at least one current backup first. In an ideal world, you’d have an updated Time Machine backup, a bootable duplicate, and an Internet backup. That way, if something goes wrong as thousands of files are moved around on your drive, you can easily restore.

After those tasks are complete, make sure you don’t need your Mac for a few hours. There’s no telling exactly how long the upgrade will take, especially if it has to convert your drive to APFS, so never start an upgrade if you need the Mac soon.

Initiating the upgrade is just a matter of opening System Preferences > Software Update, clicking the Upgrade Now button, and following the instructions.

After You Upgrade

Part of the reason to set aside plenty of time for your Big Sur upgrade is that there are always clean-up tasks afterward. We can’t predict precisely what you’ll run into, but here are a few situations we’ve noticed:

- macOS will probably need to update its authentication situation by asking for your Apple ID password, your Mac’s password, and if you have another Mac, its password too. Don’t worry that this is a security breach—it’s fine.

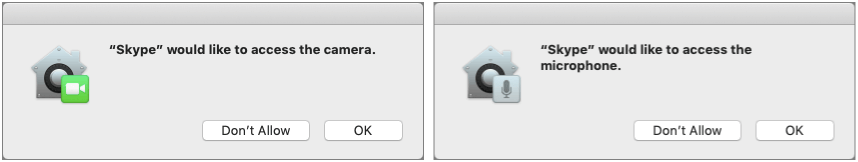

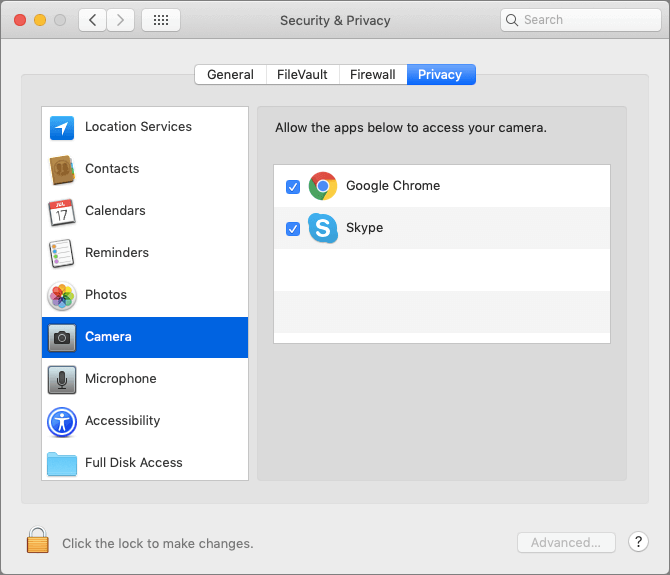

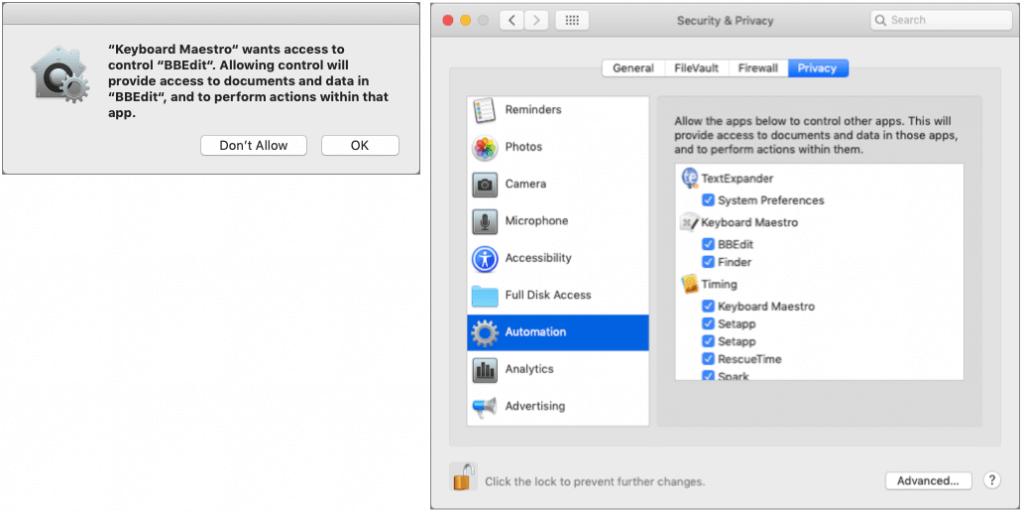

- Some apps may have to ask for permission to access your contacts and calendar even though you previously granted permission. Again, that’s fine.

- If you use your Apple Watch to unlock your Mac and apps (and you should, it’s great!), you’ll need to re-enable that in System Preferences > Security & Privacy > General.

- If you use Gmail or Google Calendar or other Google services, you may need to log in to your Google account again.

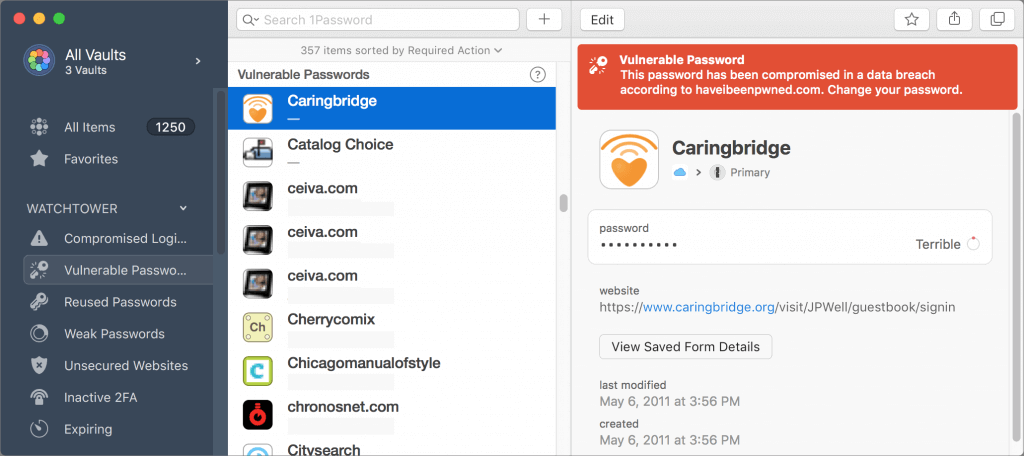

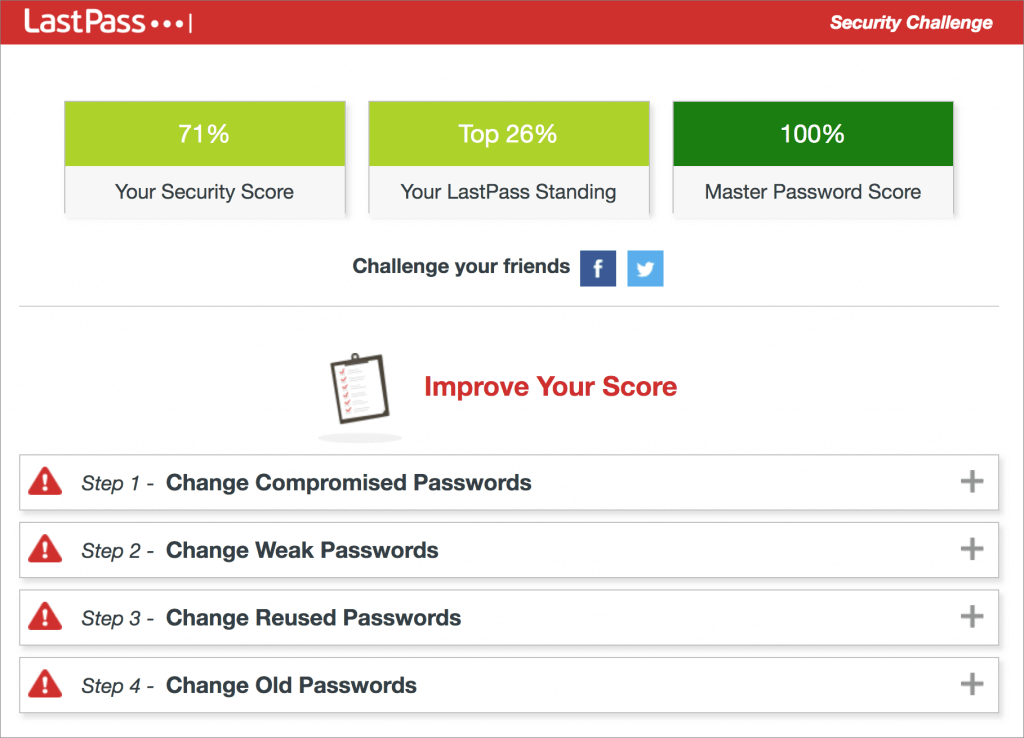

- Websites that usually remember your login state will likely require that you log in again. If you’re using a password manager like 1Password, that’s easy.

- You may have to re-enable text-message forwarding to your Mac on your iPhone in Settings > Messages > Text Message Forwarding.

- Those who use Backblaze for Internet backups will find their backups have been “safety frozen.” Follow these instructions for thawing your account.

Finally, Time Machine in Big Sur now supports and prefers APFS-formatted drives, and all of Apple’s development is going in that direction now. You can keep using your existing Time Machine backup in Big Sur, but after you’re confident that everything is working well—and you have another backup—it’s worth removing your Time Machine backup drive in System Preferences > Time Machine > Select Disk, reformatting the drive as APFS in Disk Utility, and restarting the backup in the Time Machine preference pane.

With all that housekeeping done, it’s time to check out all the new features in Big Sur!

(Featured image based on originals by Apple)

Social Media: Should you upgrade to macOS 11 Big Sur? There’s no need to do so yet, but it should be safe for most people, so if you’re excited about the new look and the new features, this is a good time to upgrade. Read on for our pre- and post-upgrade tasks.